I told myself I wasn’t going to post political or social issues here.

It seems a little self-indulgent for the head of a football blog.

Besides, that’s why the comments exist.

However, this isn’t ‘just another school/walmart/church/concert shooting’.

[How fucked up is this country to be thinking that way?]

This shooter deliberately targeted 345 Park Avenue, i.e., NFL Headquarters.

This shooting is football and NFL related as the motive is preliminarily cited as CTE.

More specifically.

NEW YORK (AP) — A gunman who killed four people at a Manhattan office building before killing himself claimed in a note to have a brain disease linked to contact sports and was trying to target the National Football League’s headquarters but took the wrong elevator, officials said Tuesday.

Furthermore, the assailant played football at Granada Hills, maybe a 30 minute drive from L.A., so it hits close to home.

Needless to say, condolences to the victim’s family, friends and community, but refraining ‘condolences’ and ‘prayers’ for the Ntheen fucking time feels empty and frankly self-serving.

So here we are – AGAIN – with a myriad of emotions.

And the bigger question: what can we do about it?

Well, I’m not going to pretend I can solve everything. Honestly, I’m torn on the gun issue.

Here’s my stream-of-thought inner debate when a shooting occurs.

‘Fuck. AGAIN – who are these sick cucks!?’

‘There’s gotta be a way to stop this’

‘Take away the guns’

‘oh yeah, well EVERY government has eventually turned on its own ppl. Taiwanese would probably like to own some ARs for when the Chinese come a-knocking’

‘yeah, like ARs are going to do much against Apaches, state of the art drones, artillery, 4rth gen jets, satellites, aircraft carriers, and a co-ordinate professional military’

‘AKs beat the U.S. in Nam…’

‘This ain’t Nam, and it ain’t 1968’

‘True. Those gangsters down the street strapping and staring me down wouldn’t mind if I can’t legally buy a gun cuz their AK is hot anyways’

And round and round we go… at the end of the day, it’s just more cold bodies, warm tears, and a societal sense of numbness, futility and failure.

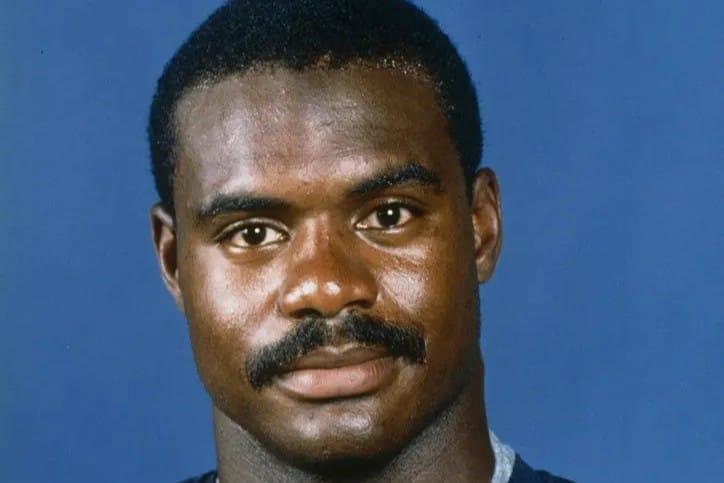

If you don’t recognize the man above, I can’t say I blame you.

Yet he’s the Dr. who the NFL tried to ruin because of his research on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) which the NFL, much like Big Tobacco, KNEW was far more dangerous than they admitted publicly.

“After Omalu published his findings, league doctors assailed his research — even going so far as to issue a letter calling for a retraction. Omalu said he was stunned to learn about the demand, afraid his career was coming to an end. He poured himself a shot of Johnnie Walker Red and “just gulped it down” before reading the letter.” – PBS

Dr. Bennett Omalu even had Will Smith play him in “Concussion.”

The NFL considered Omalu an existential threat:

“The doctor’s response, according to Omalu: “He said, ‘Your work suggests or is suggesting or is proving that football is a dangerous sport, and that if 10 percent of mothers in this country would begin to perceive football as a dangerous sport, that is the end of football.’” – PBS

Most of us know the gist of the NFL trying to bury the CTE consequences, but in short

It was evil.

Just like Big Tobacco.

The NFL hacks sold their Hippocratic oath for 30 pieces of silver, vacations and country club memberships.

Though if you want a refresher, check out the doc:

League of Denial: the NFL’s Concussion Crisis

It was a punt return. Our backup center/long snapper somehow broke free like a cheetah in the Serengeti, or more accurately, like the freaking Juggernaut.

The punt returner made a move then bolted.

Craaaaaackkkk

Everyone collectively gasped, “ooooooooh…”

You can hear that collision in the nosebleeds.

It’s the type of hit that gets everyone amped and used to make the ESPN highlight reels.

Then our teammate began jogging to the sideline.

THEIR sideline.

You can see them initially confused, then start waving at him, pointing to us.

He stops for a second or two, then does a 180.

Right away our coaching staff knew.

The assistant coach [not a Dr.] began asking him questions.

“Do you know where you are?”

“Do you know your name?”

“Do you know your birthday?”

“Follow finger…”

You can see the visible frustration in his glazed eyes. The hamster wheel in his brain was spinning but going nowhere.

He KNEW he knew the answers to the questions yet couldn’t answer.

He kept muttering, “Fuck. Fuck.” disappointed in himself, likely terrified.

—

Oddly enough, I’ve seen nearly this exact same reaction before – in a car accident.

That was the first time I can remember [or not] losing consciousness. One second I was waving goodbye to a girl from the back seat.

Next second I wake up with 3 other ppl in the truck groaning with the driver still out.

I shook everyone and told them to get out. I had no idea if we were trapped, or if the truck was on fire, or what. I just saw the hood of the car was crunched like a candy wrapper.

The driver took longer as he was beyond dazed.

Apparently I had flown and cracked the windshield with the back of my head which ended up needing stitches.

The paramedics arrived and asked the driver basically the same questions as the coach.

Place – name – DOB…

Similar reaction as our Center: blank stare. Searching eyes. Exasperation almost to point of tears.

They wrapped us in neck-braces, loaded us on gurneys and ambulanced us to the hospital.

——

Our center/long-snapper was pulled for the game.

Come Monday, he was back at practice ramming his helmet in Oline drills considering himself “lucky” he didn’t suffer any “real” injury.

In high school, he was pretty square. Not a nerd or soft, just meat and potatoes with a side of feisty like most centers. I was probably a bigger fuckup than him at that point – flunking classes, wearing torn jeans against dress code, hitting up ditching parties, beer runs, etc.

Years after high school, I heard he got into some trouble. Rumors of violence and prison.

Sometimes, I wonder…